The Great Valuation Game: Creating the illusion of expertise

The valuation profession understandably promotes the idea that a “valuation” represents an independent, objective (and presumably unbiased and reliable) estimate of the price at which a capital asset would sell for in a market transaction. The profession has seemingly defended the independence and objectivity of its work through an argument parallel to one the AICPA has presented for auditors: Although auditors are paid by their clients and, therefore, might be perceived as lacking (economic) independence, they are independent in fact because [well, after all] they are ethical professionals who also care deeply about their reputations. I personally find the argument fairly compelling, in principle; mainly because auditors tend to do quite well financially and the economic effects of reputational damage to auditors can be severe, to put it mildly. The problem is, apparently, in the application of the principle: Empirical evidence on accounting and auditing scandals sadly suggests something like “Oops! Some folks in our profession made some auditing mistakes … not because some folks lacked some independence or objectivity or professionalism or competence, but because–hey–they’re only human.” Hope and Belief Springs Eternal … contrary to any sane evaluation of the evidence.

But what about the valuation profession? Where are the valuation scandals; where are the valuation failures? A reasonable question, no doubt, and one I think most valuation professionals proudly welcome. I think the consensus response would be something like the following: “Sir! Please! We are not only professionals who adhere closely to various valuation standards and our learned colleagues’ best practices. We have no scandals! We are, in short, sir, experts!” (What?! Not one scandal? That’s a bit odd, isn’t it?)

This valuation profession’s message is plausible and clever, and stems from the idea that experts are in such high demand that they don’t need to stoop to the modi operandi of the common professionals who must do what their clients want. That is, experts by their nature and circumstances are intellectually and economically independent of their clients, and therefore care only about creating and maintaining their expertise and their reputations as experts.

This is precisely the Great Valuation Game: Creating the illusion of expertise. Please read on … (and it might be helpful to read my previous, related article “Avast! Are we not valuation analysts? No. We are valuation assumers.“ to understand the particular worldview presented here.)

1. Understanding valuation expertise

Expert testimony defined. It’s always best to be clear on exactly what we’re speaking about, so let’s start by examining the concept of expert testimony based on the following rule used in the U.S. Federal Court system:

Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witnesses

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_702

A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if: (a) the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue; (b) the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data; (c) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and (d) the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.

.

Expert testimony is based on logos; not ethos or pathos. It’s important to recognize that federal court judges use the rule to determine whether the testimony of an “expert” is admissible as “evidence” in court. The rule stems from the need to filter out unsupported opinions of seeming experts in court testimony. Without such a rule it becomes more likely that juries would be overly influenced by the ethos and pathos of the supposed expert’s testimony, rather than by the logos of the testimony. Roughly speaking, Federal Rule of Evidence 702 (FRE 702) requires testimony to be sufficiently scientific to be admissible as evidence in court.

Expert testimony and expertise are distinct concepts. FRE 702 essentially distinguishes between an expert and expert testimony. This is important because an expert is a person with a high level of knowledge, experience, and skills in a particular domain; but such characteristics of a presumed expert are unobservable. In contrast, expert testimony is essentially observable as defined under FRE 702: Expert testimony is that which is provided by a person with sufficient, relevant knowledge, skills, experience, training, and education that reliably applies reliable principles and methods to sufficient facts and data.

Degrees and credentials are not expertise. Knowledge, skills, experience, training, and education are essentially unobservable because we cannot see what is in anyone’s mind, and this includes experts with advanced university degrees and copious credentials. We all learn … and we all forget too. Degrees and credentials might be impressive and prestigious, but they mean quite little if we are interested in accurate, reliable valuation estimates.

Although degrees and credentials seem to indicate expertise, there is no necessary causal link between credentials and performance: History is littered with examples of professionals in law, medicine, science, accounting, and finance with excellent degrees and credentials that have one way or another failed in their professional responsibilities. This seems to be precisely the reason that FRE 702 focuses on the quality of expert testimony rather than on expertise per se. It’s impossible to evaluate the unobservable things in the mind of an “expert,” but we can evaluate the objective things that an expert says and writes. We can evaluate testimony, in whatever form, because it is basically objective: we can at least agree on what was said and written, even if we do not agree on its truth or falsity.

How to evaluate expertise. If we are to meaningfully evaluate expertise we must evaluate things that are objective; and FRE 702 outlines what these things are: objectively reliable theory and methods that are objectively and reliably applied to relevant, objective facts and data. In the context of evaluating valuation expertise, this can be summarized as follows:

Valuation expertise can be evaluated by examined the extent to which valuation estimates are based on (i) methods objectively derived from empirically-supported economic theory and asset pricing theory, (ii) relevant, objective economic and capital market data, and are (iii) demonstrably accurate and reliable.

Those with substantial legal experience will recognize that this is basically just a restatement of the Four Corners Rule, which states that the meaning of a contract is determined solely by the text of the contract (because only the text of the contract is observable and, therefore, objective). The meaning of a contract is not determined by the unobservable intent of the contracting parties. By analogy, under FRE 702 and the above statement, valuation expertise should only be evaluated on the basis of what is spoken and written by the valuation professional with respect to how the valuation estimate was derived; not on the basis of some kind of unobservable expertise.

How can an expert’s valuation opinion (or conclusion) be subjective while at the same time the related valuation estimate is objective? The answer is that the valuation estimate is objective to the extent the expert fully discloses all significant facts, data, methods, and assumptions used in developing the estimate; usually in a written report. It is not the case that a valuation estimate is objective simply because it is written; substantial full disclosure is necessary for objectivity … and objectivity is necessary to evaluate expertise; at least this is what is suggested by FRE 702.

Opinions are often subjective; estimates should be objective. Apparently because finance and other business professionals usually do not distinguish between valuation opinions and valuation estimates, there is a common misconception about valuations that can be summarized as saying something similar to “Yeah, well, that’s just, like, your opinion, man.” Many people in finance and business think all valuations are subjective opinions, which is not true. Consider how observable, objective facts and data can be used to generate either a subjective opinion or an objective estimate:

“So what?” the typical valuation professional says in response to the above discussion, “this is exactly what we do! We provide objective valuation reports based on objective, reliable valuation principles and methods!” Au contraire, I say … and I have said so before as well. I’ve previously asserted that valuation experts often use professional judgment in a way that–to an untrained observer–seems objective and observable, but is not. Valuation experts can use professional judgment to select valuation methods and data in a way to unobservably bias valuation estimates: to people with low levels of valuation expertise, unobserved choices among valuation methods and data are unobserved. In short, silent evidence is silent.

Because this is contentious point, we need to explore the ideas of observability, objectivity, and expertise more carefully to come to a reasoned conclusion.

2. Understanding valuation professional incentives

How does a valuation professional develop the public perception of his or her expertise? Degrees, credentials, and publicly-observable experience help, of course, but these are somewhat superficial indicators of expertise as I allude to above. To answer the question more fully, we need to explore how capital market asset prices are set by buyers and sellers.

Observable market prices depend on subjective valuations. Note that observable (objective) prices of capital assets depend on the unobservable (subjective) valuations of the buyer and seller:

At the fundamental level, value is always subjective: We cannot see inside people’s minds; and this is true whether the person is the seller of a capital asset or a valuation expert. In contrast, valuation estimates are objective to the extent they are written and the significant valuation inputs, assumptions, etc. used in developing the estimates are disclosed. So, value is necessarily subjective; a valuation estimate can be objective.

Seller information sets, valuations, and market prices. If capital market price depends on the subjective valuations of the buyer and seller, on what do their subjective valuations depend? In short, the buyer’s and seller’s respective valuations depend on their respective information sets. Focusing only on the seller’s information set, if the seller’s valuation of the capital asset is based on an information set comprised of a biased valuation–in contrast to an unbiased valuation, which can be defined as the most accurate valuation estimate available–then it can be shown (you can trust me on this) that the resulting observable capital market price will be below the unknown and unbiased valuation estimate:

It is not obvious that a biased valuation is usually lower than an unbiased valuation but–as will be discussed shortly–valuation experts generally have the incentive to bias valuation estimates downwards, so I will ignore discussing the alternative case for simplicity. Put concisely, ceteris paribus, a downwardly-biased seller valuation results in a lower observable market price than a price based on an unbiased seller valuation:

Unobservable discretion over valuation estimates. Sellers’ information sets are generally comprised of either valuation opinions or estimates provided by some type of expert–M&A advisors, enterprise valuation consultants, etc.–and such valuations can be characterized either as unbiased or biased:

Valuation estimates can be biased in an unobservable way, as suggested above, because neither the actual expected price of the capital asset nor the estimation error are observable. Because of the combined uncertainties over the expected price and estimation error, the seller cannot observe or infer the discretionary bias introduced by the valuation expert. It is also the case the the valuation expert might not even know of the existence and magnitude of the his estimation bias. For example, he might be following the biased estimation practices of his professional colleagues; thinking he is using “best practices.”

The idea that the components on the right-hand side of the biased valuation estimate equation are unobservable is quite subtle, but can be understood intuitively: If it were possible to either observe expected price or develop accurate, highly reliable estimates of expected price, then it would be obvious that the expert’s valuation estimate was either wrong or biased (or both). But when expected capital market price is unobservable and difficult to estimate, which is especially the case in capital assets sold in private market transactions, valuation experts have substantial discretion over choice of valuation methods and data; and this gives them substantial discretion over biasing the valuation estimate … and this bias (I assert) is usually negative, in the sense that it lowers the reported valuation estimate.

How valuation expertise is–and is not–commonly perceived. Experience suggests most professionals–even valuation professionals–perceive valuation using the simple and seemingly common-sense criterion of the extent to which the observed market price of the capital asset equals its estimated value in combination with a reasonably short time to sale:

The idea of why this might make sense to evaluate expertise in this way is captured in things I’ve often heard sellers say similar to “Wow! My M&A advisor is amazing! He said my company was worth about $50 million, and he sold it in 4 months for $ 48 million. That guy really knows what he’s doing!” But there is a serious problem with evaluating valuation expertise this way: Knowing what a capital asset is likely to sell for to a specific set of buyers in a short-period of time generally does not represent the opportunity cost of a capital asset. The opportunity cost of a capital asset is what an equivalent asset with the same risk-return characteristics would sell for in an open capital market where buyers compete to acquire the asset.

More simply, the problem with evaluating expertise in this way is that if the sell-side M&A advisor knows that a specific set of buyers will buy a capital asset for an expected ROI of about 30% but–unknown to the seller and perhaps even the M&A advisor–the same asset would sell in the open market for an expected ROI of about 12%, the seller will unobservably lose money; a lot of money. (It is hopefully obvious that the lower the seller’s valuation is, the faster and easier it is to sell the asset. And for the reader who doubts that real world pricing differentials correspond to buyer target ROI differentials as large as 30% – 12% = 18%, I can assure you I have directly observed this in capital asset transactions ranging into the 100s of millions USD.)

In contrast, actual valuation expertise is evaluated in a quite different manner, as is suggested by FRE 702 above:

The extent to which a valuation professional demonstrates actual valuation expertise depends on the knowledge of valid valuation theory and methods, and the ability to apply them objectively to relevant data to obtain a demonstrably unbiased valuation estimate, which is based on an unbiased estimate of opportunity cost of capital.

Valuation expert incentives, based on this discussion and ignoring any psychic costs associated with violating ethical norms, can be summarized as follows: Because (1) valuation experts are most often paid for perceived, observable expertise rather than for actual, unobservable expertise and (2) such perceived expertise depends on unobservably lowering valuation estimates, it follows that (3) valuation experts have incentives to downwardly bias valuation estimates by using a combination of (i) semi-observable discretion over selection of valuation methods and capital market data and (ii) unobservable discretion over application of the methods to the data.

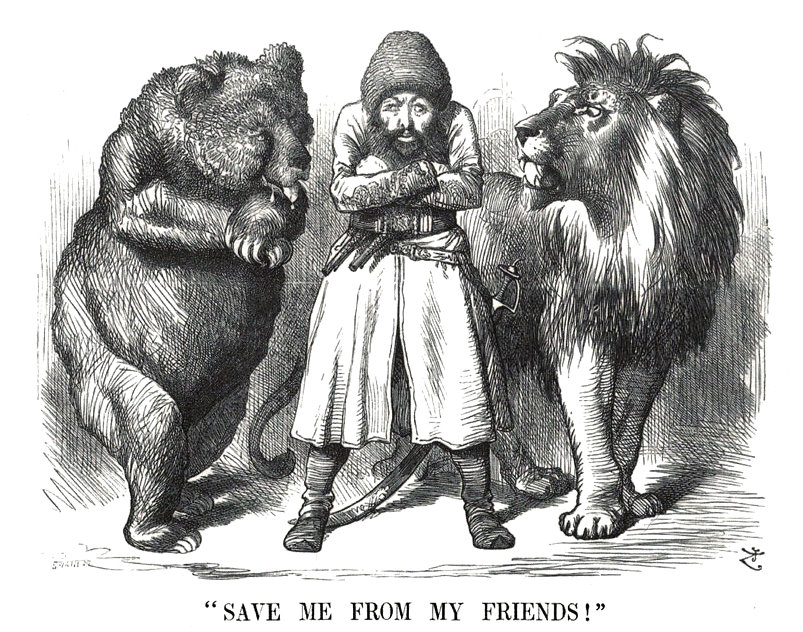

A simpler, more intuitive way to think about valuation professionals’ incentives is to recall the case of brokers of real estate: neither the sell-side broker nor the buy-side broker gets paid unless the property is actually sold. So, in a very real sense, to the extent both buy- and sell-side brokers need to be paid (in money), they are both working for the buyer (who has the money): no sale, no brokerage commission. This also true for professionals on both the buy- and sell-sides of a capital asset transaction: no sale, no brokerage commissions … and, by extension, if the brokers don’t get paid because a valuation expert shows the value of a capital asset is substantially more than the final buy-side offer price, then the valuation expert develops a poor reputation among brokers: “Dude! Narc! If you show the seller what his company is really worth and none of us gets paid, I will make it my mission in life to tell everybody I know in the M&A industry that you’re an idiot and killed this deal!” Sadly, as is often the case in the grand scheme of human endeavors, one must go along to get along.

What I find particularly fascinating about all this is that valuation professionals often seem to be maximizing such incentives without even realizing precisely what they are doing. To understand how this can be and how the illusion of expertise can be created, it is best to explore an example of the valuation illusionist at work.

3. Creating the illusion of valuation expertise

I will now show–step by step–how a valuation illusionist can create the perception of expertise. There are actually a number of different ways that valuation experts can exercise discretion over valuation methods and data in a way resulting in unobservable bias, but I will just focus on the most common method based on my experience.

Selecting the valuation method. Professional valuation practice suggests that there are three general approaches to estimating value: the (1) income approach, (2) market approach, and (3) cost approach. In contrast, asset pricing theory–on which all enterprise valuation practice is necessarily based–suggests that the value of any capital asset is determined by the present value of expected future cash flows attributable to the asset discounted at the risk-adjusted expected market rate of return on an asset with equivalent risk-return characteristics (i.e., the discount rate is the opportunity cost of capital for the asset). So, according to asset pricing theory, value is determined by the income approach even if under certain circumstances the market approach and cost approach result in the same valuation estimates:

And here is where the unobservable magic of the valuation illusionist begins: Because in theory any of the three valuation approaches is equivalent, the illusionist will select the method that most closely aligns with his incentives. This usually turns out to be the market approach because it tends to allow the illusionist more discretion in introducing downward bias into valuation estimates. The reason for this is that the market approach actually ignores asset pricing theory by using capital market transaction data on so-called “comparable companies” without clearly demonstrating the sense in which the risk-return characteristics of the companies are such that the data is relevant or useful in developing an unbiased valuation estimate. At the same time, the market approach seems valid because it can be equivalent to the income approach, it also has a veneer of professional authority and empirical research to give it the appearance of validity. But the fact that the market approach can be equivalent to the theoretically-valid income approach does not mean it is necessarily so.

Consider the following summary showing the essence of the market approach in the context of estimating equity value, which generally uses observable price-earnings (P/E) ratios of so-called comparable companies:

The implication here is that the valuation estimate is a function of earnings and is conditional on the average P/E ratio of the selected “comparable companies”:

The shrewd observer and consumer of valuation estimates would naturally ask the valuation illusionist, “What exactly do you mean by comparable companies?” The valuation illusionist hides behind the veil of expertise and says something similar to “I am a trained valuation expert with credential X and Y years of experience in valuing these types of companies. I carefully read the industry and financial reports of companies and, based on my knowledge and experience, the risk-return characteristics of the comparable equity securities I’ve used are substantially equivalent to those of equity interest i.” Very impressive sounding, indeed. But as we’ve seen, persuasion by an appeal to factors suggestive of expertise does not constitute actual valuation expertise.

Selecting capital market data. If we accept the valuation illusionist’s statement of expertise at face value–which most people do, by the way–he can generally select “comparable” equity securities at will by searching the available hyperspace of equity market data and finding precisely the right sample of P/E ratios of “comparable companies” that result in a downwardly-biased estimate.

To develop intuition for how the valuation illusionist works, consider the special and (not-so-)hypothetical case where illusionist is a sell-side M&A advisor. The advisor develops the illusion of valuation expertise through carefully advising client executives on the value (expected price) for the client company and in assisting the executives negotiate the sale of the company at or near that value. The first (unobservable) step the advisor takes is to call around to his network of other M&A advisors and, even better, of corporate development directors who manage strategic acquisitions for their employers. From discussions with these contacts, the sell-side advisor develops an estimate from a specific, identified set of potential buyers of his client company about what they are readily willing to pay, which stated in terms of an average of P/E ratios this would be …

Armed with this unobservable-to-the-seller information, the advisor then searches the capital market data hyperspace to identify a usually small sample of equity securities that both (i) can be plausibly characterized–in a qualitative way–as “comparable” to the advisor’s client company and (ii) have an average P/E ratio that approximates the expected price the unobservable set of potential buyers are willing to pay. The valuation illusionist then just “helps the client to find a buyer and negotiate the selling price”:

Perhaps quite surprising to the client, but not at all to the valuation illusionist, the valuation estimate that was provided to the client–as if by some uncanny feat of prescience–closely approximates what the buyer is willing to pay … and it all happened much faster than the client executives expected. Simply amazing, no?!

It’s important to not get lost in the math and understand in simple way what’s happening in the example: The sell-side M&A advisor–the valuation illusionist–is, unbeknownst to his client, contacting potential buyers and simply asking them what they want to pay for his client company. Having a clear idea of what specific buyers will likely pay, he then carefully chooses a sample of capital market data that results in a valuation estimate very close to what the potential buyers said they would pay. And then (he acts like) he negotiates fiercely to get the full price equal to the value estimate he has provided to his client. And voilà! He has apparently accomplished his task admirably and shown that he is, indeed, a Valuation Expert (Illusionist).

Observably adjusting the valuation estimate. All this is not to say that there is little expertise being demonstrated by the valuation illusionist. It’s just that it’s not valuation expertise per se; it is expertise at selling a capital asset for less than its value in a way that’s unobservable to clients. Which brings us to another important tool available to the valuation illusionist: the discount for lack of marketability (DLOM); a somewhat poorly defined concept related most closely associated with capital assets not traded in open, liquid markets. Because the observed capital market data selected to develop the biased valuation estimate is still sometimes higher than the price range suggested by the unobservable set of potential buyers, the valuation illusionist can observably reduce the valuation estimate using a DLOM:

Adjusting the valuation estimate using a DLOM is a particularly effective technique for the valuation illusionist because a broad range of discounts from about 10% to about 35% can be justified by making reference to the empirical capital market research on marketability / liquidity discounts (cf. Damodaran 2005) and developing a qualitative explanation of why the selected discount is appropriate in the client company’s circumstances.

I’ve termed the above expression The Grand Illusion of Valuation Expertise because the observable adjustments to valuation estimates such as the DLOM has the appearance of objectivity. But there often is nothing “true” about the adjustments; neither the valuation illusionist nor the client know the extent to which the adjustments represent the opportunity cost of marketability, liquidity, etc. It is the grand illusion of objectivity covering the illusion of objectivity obtained from a sample of publicly-observable P/E ratios, which were selected in an unobservable way to meet the expected price a buyer from a specific, unobservable set of potential buyers told the valuation illusionist he would be willing to pay. Ouch.

On the unwittingness of valuation illusionists. Before the reader thinks I am calling the valuation illusionist evil–which I most certainly am not–I want to emphasize that he is generally unaware of what he is doing wrong in theoretical terms; he is simply following his (sometimes inadequate) training in asset pricing theory and the “best practices” of his professional colleagues. To see this, consider the theoretical representation of the biased valuation estimate:

Again the idea is fairly simple: The valuation illusionist has no interest in estimating the opportunity cost of equity capital for company i per se; he just wants to estimate what the company will sell for (quickly and definitely). He does not, for whatever reason, develop an estimate based on valid asset pricing theory and is therefore perhaps unaware of what expected price based on opportunity cost of capital would be. He simply applies the method described above to obtain what is represented on the left-hand side of the equation. He is perhaps not even aware that the market approach he used based on a selection of P/E ratios is even biased, or that the DLOM might further bias the valuation estimate away from fair market value. He perhaps does not understand that substantially all modern capital markets–including private capital markets–are integrated and, accordingly, the biased selection of valuation method, capital market data, and valuation discounts result in biased valuation estimates. He thinks he estimated the value at which the company would sell and, hey, that’s what it sold for!

So the problem is that the valuation illusionist and his client are perhaps both ignorant–one perhaps willfully and one not–of what the company is actually worth in terms of opportunity cost and the unobserved capital market evidence; they make the error that Nassim Taleb calls The Fallacy of Silent Evidence.

(Note: I’ve just provided one example of how the valuation illusionist can bias valuation estimates to create the perception of valuation expertise, but the phenomenon and method is quite general. All that’s usually necessary to keep the valuation illusion methods fairly well obscured is to dazzle clients with ethos, pathos–the veneers of expertise–and highly professional-looking, long, complex valuation reports.)

4. Implications of illusory valuation expertise

When I’ve had discussions about these things with valuation professionals, M&A advisors, investment bankers, accountants and auditors, they all have a similar perspective: “What’s the problem?! Clients hired valuation experts to advise them; advisers estimated value; and advisers helped sell the companies for a price near the value estimates. The clients weren’t forced to hire experts or sell their companies at the prices the experts advised them on. It was their choice. Where is the harm?!” Oh, there is definitely harm; it’s just not easy for someone unfamiliar with capital asset valuation to see because the evidence of the harm is unseen. Read on …

Equity holder loss from a biased valuation and price. Consider the following example, which is entirely consistent with a number of mid-market M&A and private equity transactions I’ve personally participated in–after the transactions–as a consultant developing valuation estimates for purchase price allocation: A family wants to sell its 100% equity interest in a privately-held company that (in simplified terms) is expected to generate a USD $161.051M (M = million) cash flow to equity holders at year t = 5. A good estimate of the opportunity cost of capital over a 5 year horizon is about 10%, but the M&A advisor–for whatever reason–estimates a discount rate of 12% developed using the market approach method discussed in the preceding section:

The sell-side M&A advisor says something logically equivalent to “To the best of my knowledge and belief, the 12% discount rate represents an unbiased, reliable estimate of opportunity cost of capital.” The problem, once again, is that the advisor’s knowledge and belief is unobservable and he did not demonstrate that the 12% discount rate and resulting valuation estimate are unbiased and reliable. But, really, he’s an expert, right? Why would we question his expertise? The company was sold for a price very near the estimated value. Now that’s demonstrated expertise, no?

As it turns out, the family who owns the company does not question his expertise or the valuation estimate of $91.4M, and agrees to sell the company for about that price less the M&A advisor’s brokerage commission.

Valuation advisor loss from a biased valuation and price. The (now mightily offended) sell-side M&A advisor reads this article and responds: “Are you serious?! We wouldn’t do that. Not only are we professionals, but we would never do anything that would result in us losing money. Our commission is based on a percent of selling price. We have the incentive to negotiate fiercely to maximize price, and that’s what we do!” Well, maybe. Let’s determine how much the advisor lost by biasing the valuation downwards.

Consider the difference between the advisor’s commission based on the unbiased versus the biased valuation (assuming prices equal the value estimates):

See?! The advisor would never under-price the company $8.6 million because he would lose $172,000, right? He would undoubtedly work long and hard to find an unknown buyer and negotiate a price near the the unbiased value of $100M so he could earn that additional commission of $172,000, right? But he would at least sell the company for as much as possible; in this case, he asserts, it was $91.4M.

The problem with this line of thinking is that the M&A advisor in all likelihood is unaware of the unbiased estimate of the company’s value: Recall the advisor simply searched for capital market data that would support the “reasonable target price” that he knew was “reasonable” because he had already spoken with specific potential buyers. The statistical estimate depended on the advisor’s expectations; not vice versa as would be appropriate if he was hired to advise on the actual value of the company … as opposed to a price acceptable to a limited set of potential buyers from whom he had already solicited interest and quasi-bids.

The final analysis. So, who gains and who loses in this and similar M&A and private equity transaction scenarios? Consider the question from the separate perspectives of (i) the sell-side M&A advisor based on his information set, and (ii) the unbiased valuation estimate developed by the valuation consultant hired after the transaction to assist with financial reporting valuation issues. Considering the M&A advisor’s perspective in this way is important because it shows clearly his incentives and why he does not see the problems with his biased valuation estimate:

So, the advisor has a subjective gain of $1.828M and the equity holders have an unobserved loss of $8.600M. Remember: the advisor has a subjective gain of $1.828M and was not aware of his objective loss of $172,000 … because he did not estimate the unbiased value of the company. From his perspective, he was only aware of selling opportunities with the specific set of potential of buyers he obtained indications of interest and quasi-bids from at a price of about $91.4M; they were the only commission source of which he was aware. So, from his perspective, he won. The equity holders likewise believe they are winners because their company was sold for $91.4M; a price equivalent to what they believe to be the value.

So, strangely enough, both the sellers and their advisors believe they’ve achieved an optimal outcome; advisor: “I’m an expert, I tell you!”; sellers: “Yes! You, sir, are indeed an expert!” And yet they both seemingly lost money from an economic perspective. But, in fact, only the sellers lost money; the advisor was paid very well for the limited time and effort devoted to selling the company.

And what of the valuation illusionist posing as the valuation expert? Well, he is happy too: If he was the professional supplying the $91.4M valuation estimate consistent with the M&A advisor’s expected price, then the M&A advisor–an excellent source of valuation project referrals–will say to everyone, “Yes! My friend the valuation professional is indeed a valuation expert too!” Como queríamos demonstrar.

5. Demonstrating actual valuation expertise

So, finally, for the diligent, patient reader (who I sincerely thank), how is actual valuation expertise demonstrated? After all, isn’t the Silent Evidence Problem both pervasive and insoluble? Isn’t it the case that the valuation illusionist does what he does because there is no better theory or method? The answers are, in short: (i) Actual valuation expertise is demonstrated by developing accurate, reliable, cash flow forecasts, risk sensitivities, and market prices of risk using objective methods and data. (ii) The Silent Evidence Problem can be largely mitigated using modern asset pricing theories and methods. And (iii) there are better theories and methods, and they have existed for about 40 years. So, dear valuation illusionists, delay no further; true valuation expertise beckons!

MMc

São Paulo

Caveats. Please note: (i) views presented above are my own and do not reflect those of others; (ii) like anyone, I’m not infallible and am responsible for any errors; (iii) I greatly appreciate being informed of any significant errors in facts, logic, or inferences and am happy to give credit to anyone doing so; (iv) the above article is subject to revision and correction; and, (v) the article cannot be construed as investment or financial advice and is intended merely for educational purposes. MMc